A bit of history

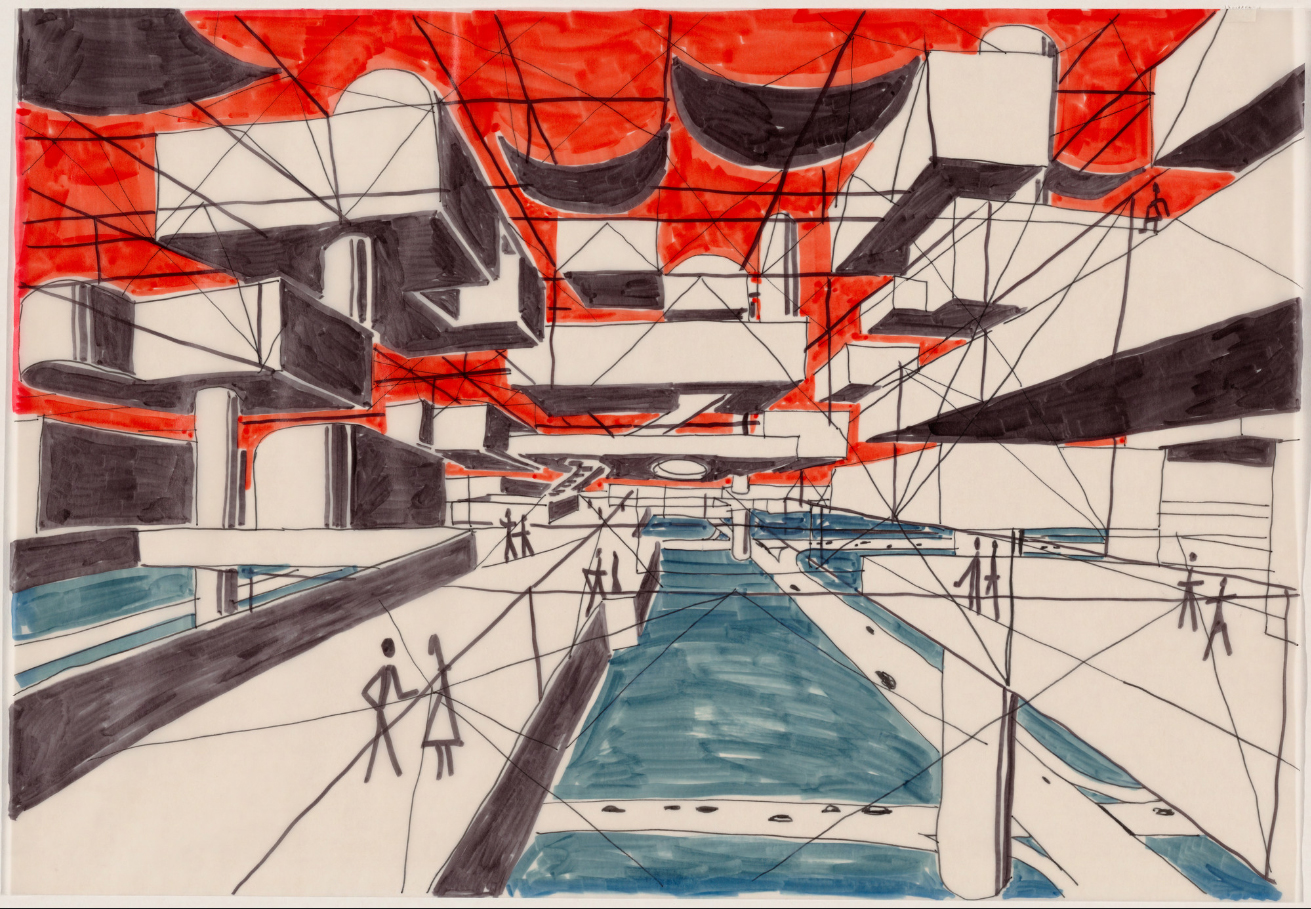

“Architecture exists today in two forms: its constructed reality, which we are going to experience physically, and then its photographed image, its drawings, its photos of even models, which come to us in publications. I put them on the same level whereas, classically, there is the real and its representation: of course, the test of truth is the constructed real. But the truth is that we have not been able to see the tenth of what we know by image.

This multiplication of images of projects that almost no one will be able to see is a source of wealth but above all it is a danger. A new status has been established for the image of architecture, of the photographic document: metonymical figure, piece that speaks louder than the whole, special effect, icon, instrument of autonomous communication, detached from the knowledge of real space.

The drawing, as its line is coded, is clearly distinct from the reality it represents. With photography, the gap between reality and image becomes very ambiguous. The photo is given for the real, and therefore the distortion is inevitable, manipulable, sometimes interesting. But a good project is a project that is more in reality than in image.

Perhaps then in the book a global coherence can be restored to us which touches on the truth of the project (a bad project can make a striking image but not a book).

Perhaps it is even only in the book that the whole relation between projection and perception can be established.”

Christian de Portzamparc

Architectural visualization is at the confluence of several artistic disciplines.

Its goal, to stage an architecture, uses knowledge and techniques coming in part from painting and photographic shooting while remaining a design and communication tool for architectural projects.

The history of this discipline is quite difficult to trace, mainly for lack of documents. Indeed, if there are many ancient, ancient and sometimes millennial architectural works, for their representations, it is difficult to find evidence older than the period of the beginnings of the Renaissance (early 13th century).

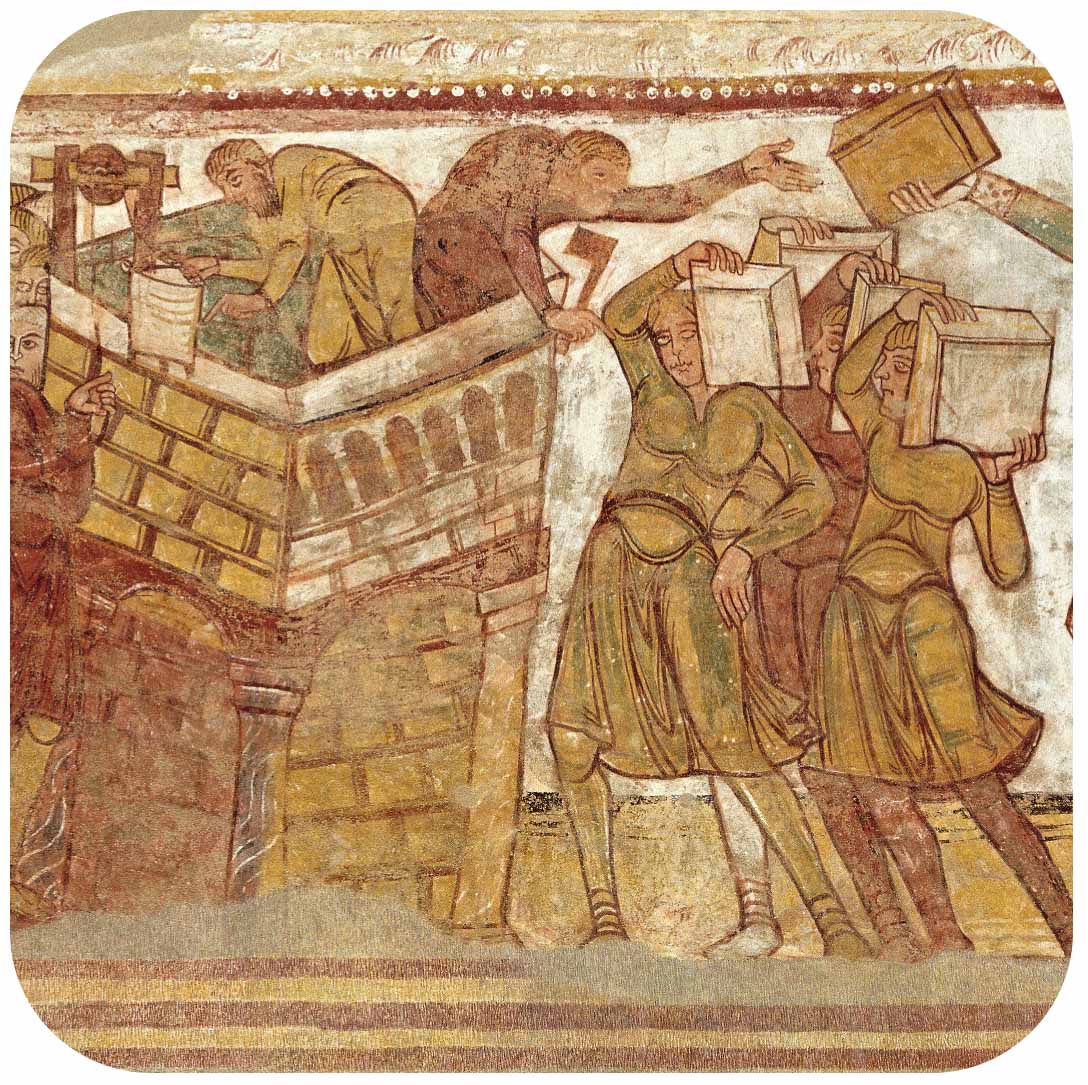

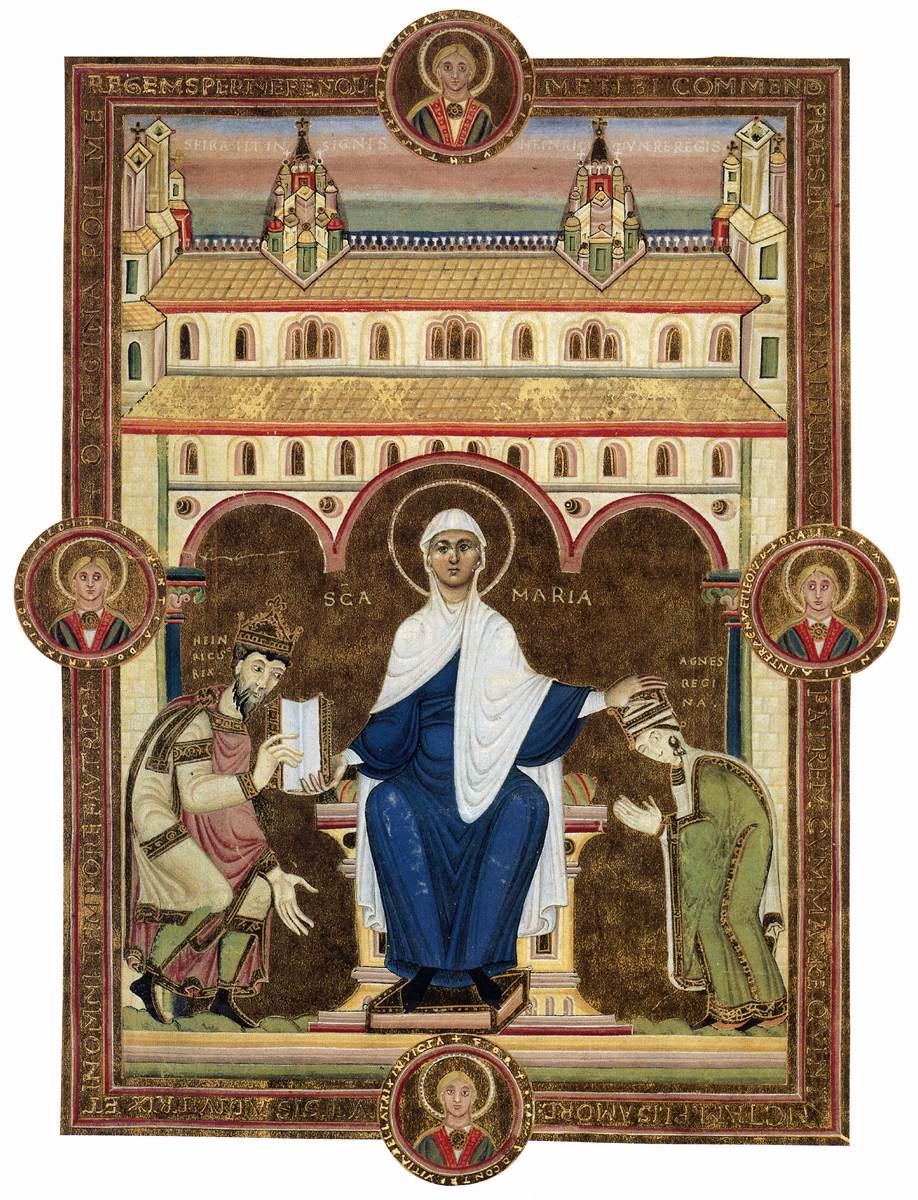

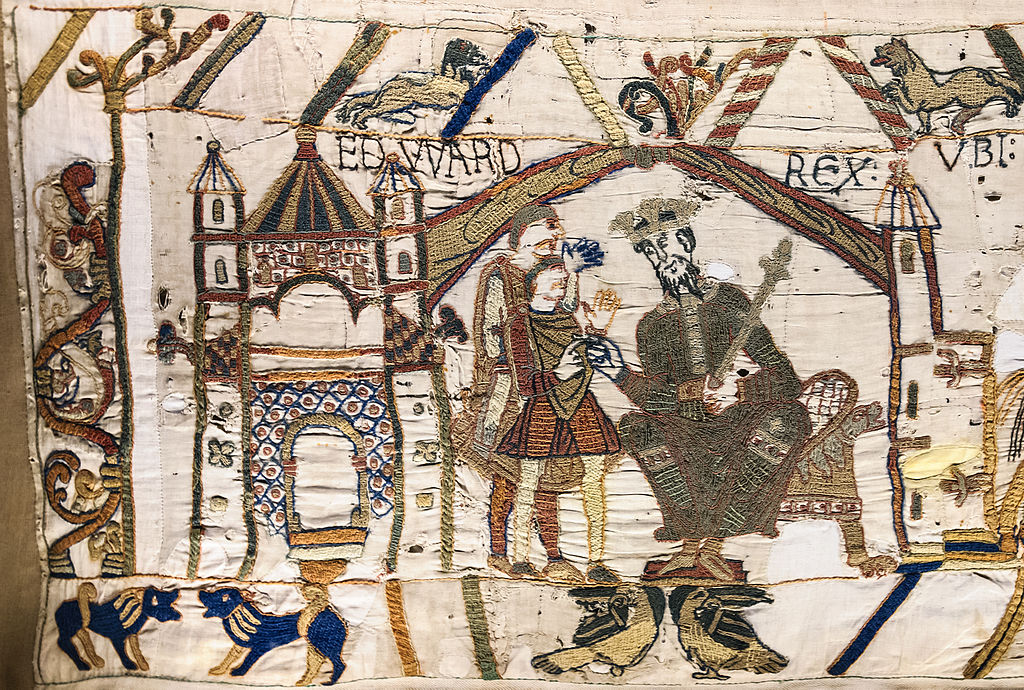

“Until the 13th century, there is no trace of representation of buildings that could be assimilated or directly comparable to what we understand today by architectural drawing. That is to say, no image where the building is the sole subject of the representation. Indeed whether in the illuminations of the manuscripts in the books of hours or in the painted frescoes, the buildings represented which are mainly religious buildings, are always part of a scene, they are always part of a composition. where the characters, the actors have as much importance, if not more, in the reading of the image as the building itself: scene of religious life, workers at work…

It is only around 1250 that drawings begin to appear approaching the criteria of comparison that we have given, and throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries they will multiply. As for perspective, we will only see its first forms appear in France later, in the 15th century.”

J.M. Savignat

top left : wall paintings from the Abbey of St Savin (86, 11th-12th century) – left ; The Golden Gospels of Henry II (1043-1046) – top right : The construction of Santiago de Compostela – Guillaume Dubois (16th century) – right : Bayeux Tapestry (1066-1082) – bottom left : Pilgrims in front of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher guarded by Saracens. The Book of the Wonders of the World. (15th century copy) – bottom right : The New Jerusalem, Apocalypse Tapestry (Angers 1373-1382)

Before this period, each trade makes sketches or side plans which will allow the good realization of the project. Most of the time these “sketches” will be made on a stone which will subsequently be used in this same construction, plaster reapplied to each version of the drawing or parchments, which therefore makes the traces of these representations particularly rare.

The creation of facade drawings only comes from a perspective of communication with the sponsors and even the public for often religious constructions.

Drawing fragments on a stone from St. John the Evangelist’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK, 13th century.

Drawing on the floor of the York Minister, 14th

Facade of the Strasbourg Cathedral, 1260

Michelangelo, drawings for the Porta Pia, Rome. 1551

The use of models is frequent and allows both to make the project understood by the customers and to serve as a reference for the various stakeholders in the construction site.

Gian Pietro Fugazza, wooden model of the Cathedral of Saint Stephen of Pavia, designed by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo, and Giovanni Giacomo Dolcebuono, cypress, maple and oak, Italy, 15th-16th century.

Model made by a team of craftsmen supervised by Antonio Labacco, Cathedral of St Peter, built according to the designs of Antonio da Sangallo, 1539-1546.

The origines

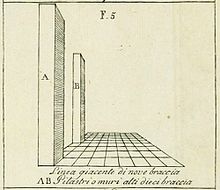

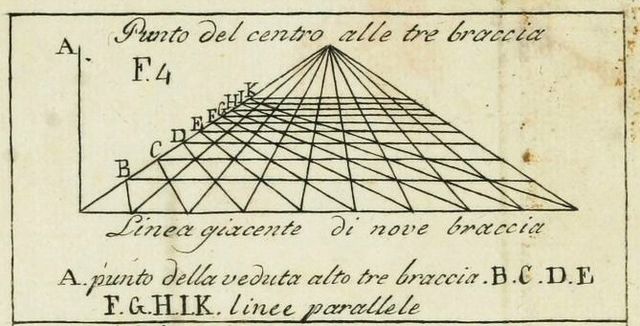

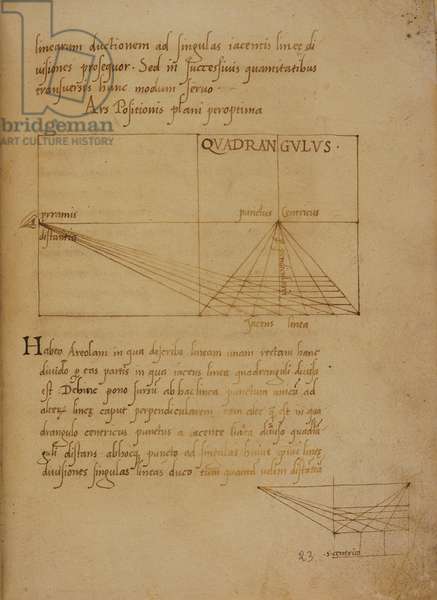

Various literary works allude to the method that Leon Battista Alberti will later formalize in 1435 in the treatise “De Pictura” where he defines the mathematical rules of the decrease in depth shortly after their “rediscovery” and especially their implementation. proof by Brunelleschi.

But the works of Plato, Euclid, Cicero and others suggest that the Greeks and Romans had knowledge of this principle although hard evidence is lacking.

De pictura (On painting) is a treatise on painting written in 1435 in its Latin version, in 1436 in its Italian version by Leon Battista Alberti. It will be printed for the first time in 1540 in Basel under the direction of Thomas Gechauff. It was the first installment of his trilogy of treatises on the major arts which were widely circulated during the Renaissance, followed by De re aedificatoria (1454) and De statua (1462).

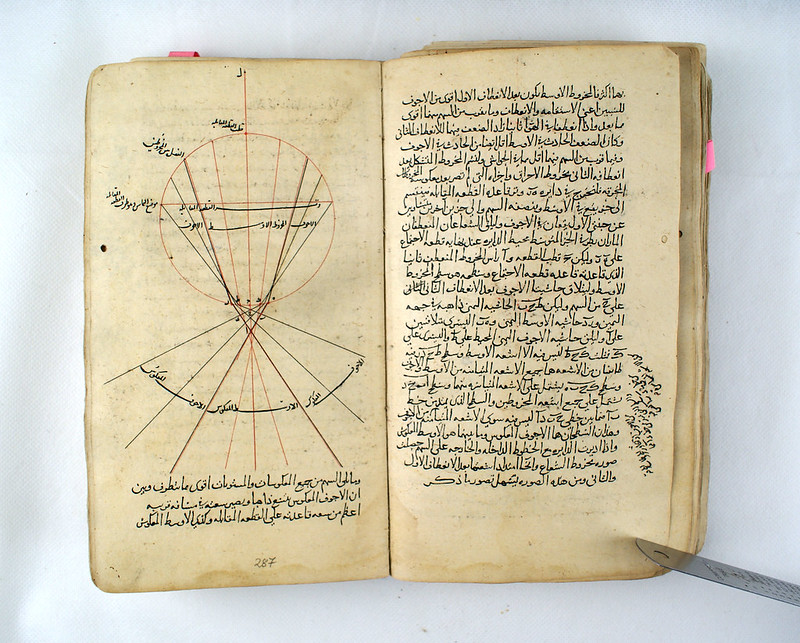

It was then writings from the Muslim kingdoms, mainly scientific treatises (Al-Kindi, De radiis stellarum, 9th century, Ibn al-Haytham, Kitāb al-Manāẓir, 1011-1021), which preserved and developed this knowledge for several centuries before to be taken up by British and then Italian authors up to Alberti.

The first steps

This fresco is considered representative of the long evolution of Romanesque and Gothic painters, who in the 14th century began to integrate a notion of relationship to reality into their work.

Artists were no longer content to repeat different codified models, as was the case during the long period of Romanesque and Gothic pictorial art where the relationship to reality was totally obscured to leave room for the narrative of images and their religious symbols.

We can see the modeling of the volumes thanks to the shadows and lights and a notion of perspective in the reduction of the different planes as they move away, two completely new elements at this time.

Left : The Faith of Giotto 1306

But it is a little later to Filippo Brunelleschi, the builder of the dome of the cathedral of Florence in 1436, that is attributed the “discovery” of the principles of perspective to one or several vanishing points in around 1425.

It was these first realistic visualizations, giving a measure of the building, its appearance and its details, which served the architect, as today, to communicate his vision to his sponsors.

Right : perspective study, by Filippo Brunelleschi, circa 1420, Florence, 15th century

Architecture in classical painting

This also marks the appearance of architecture as an element in its own right of classical painting and becomes through this use a visual work freed from its utilitarian aspect in favor of the recognition of its aesthetic and symbolic qualities.

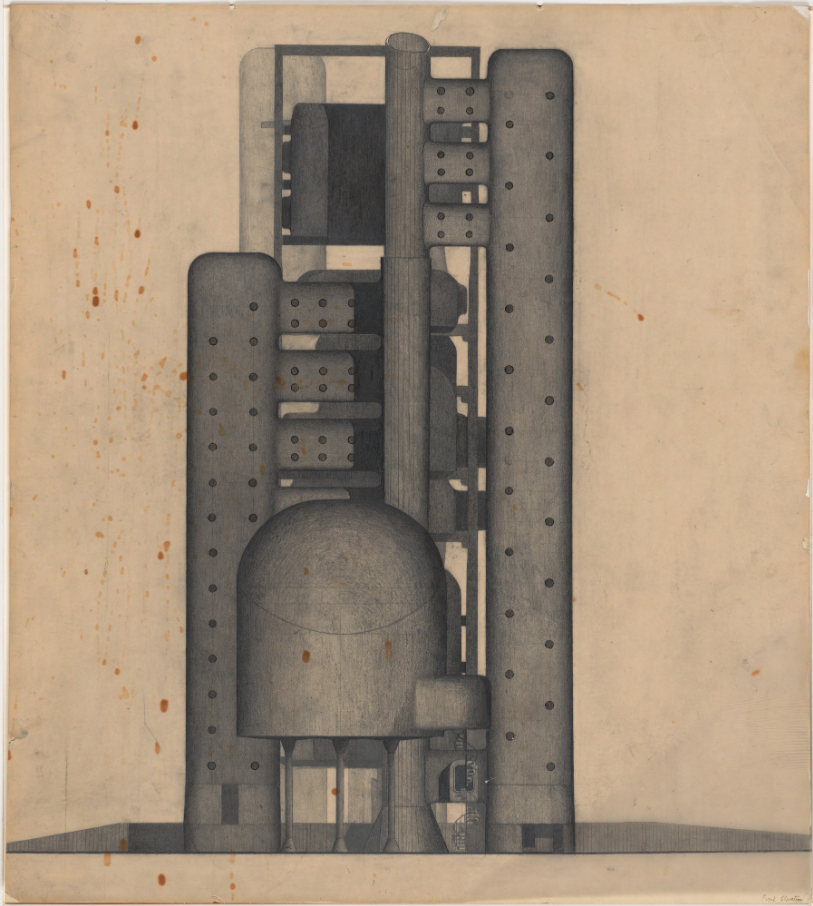

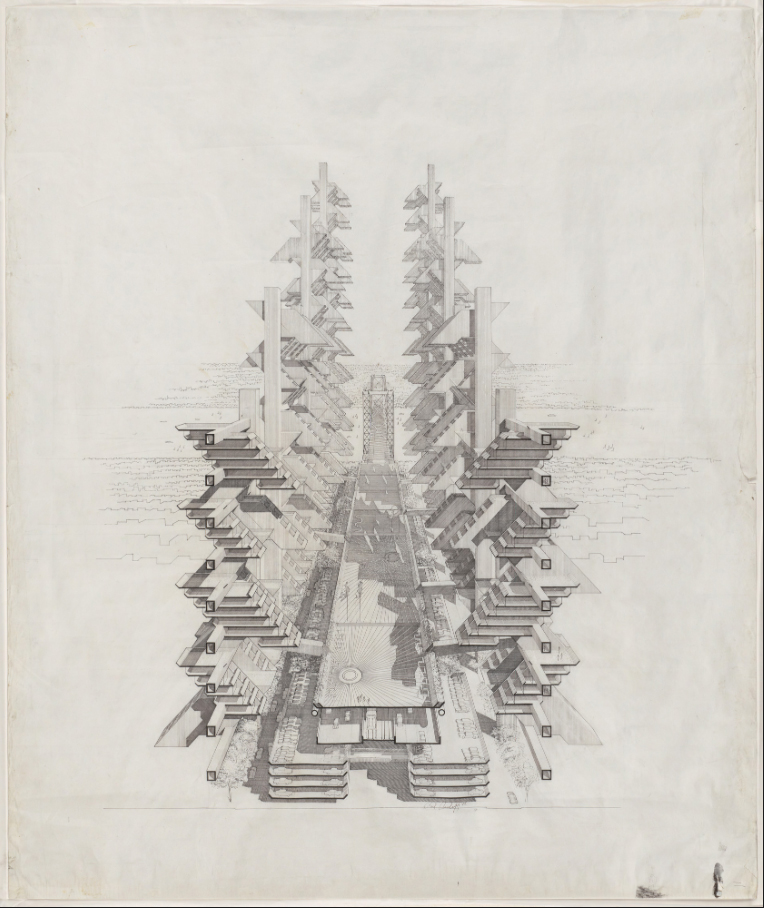

It is thanks to the techniques of perspective drawing that the architect can extract his work from structural, mechanical, budgetary and temporal constraints, to keep for a time only the most free part, an aesthetic chimera, defined only by its shapes, its proportions, its colors, its details, its ornaments, its light…

Architecture had found, renewed its best ambassador, pictorial art.

The dialogue between these two disciplines has since never known a dead time.

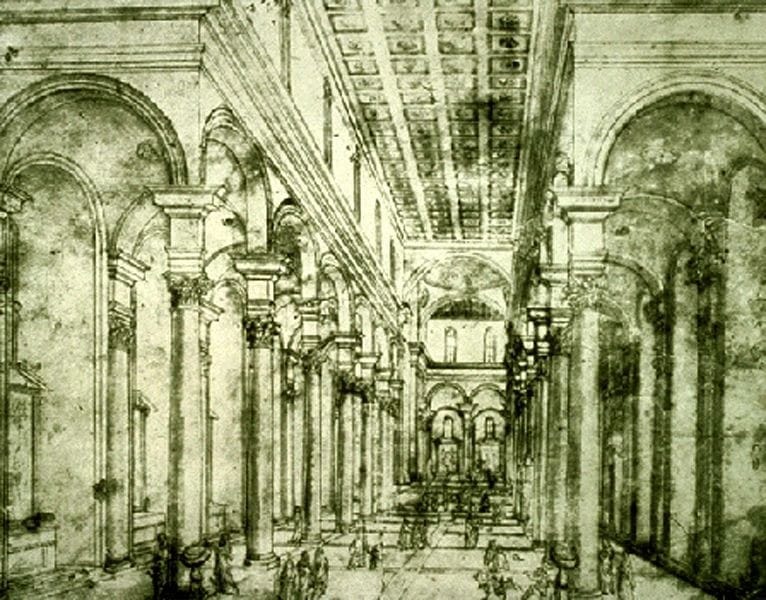

The ideal city – auteur inconnu 1223

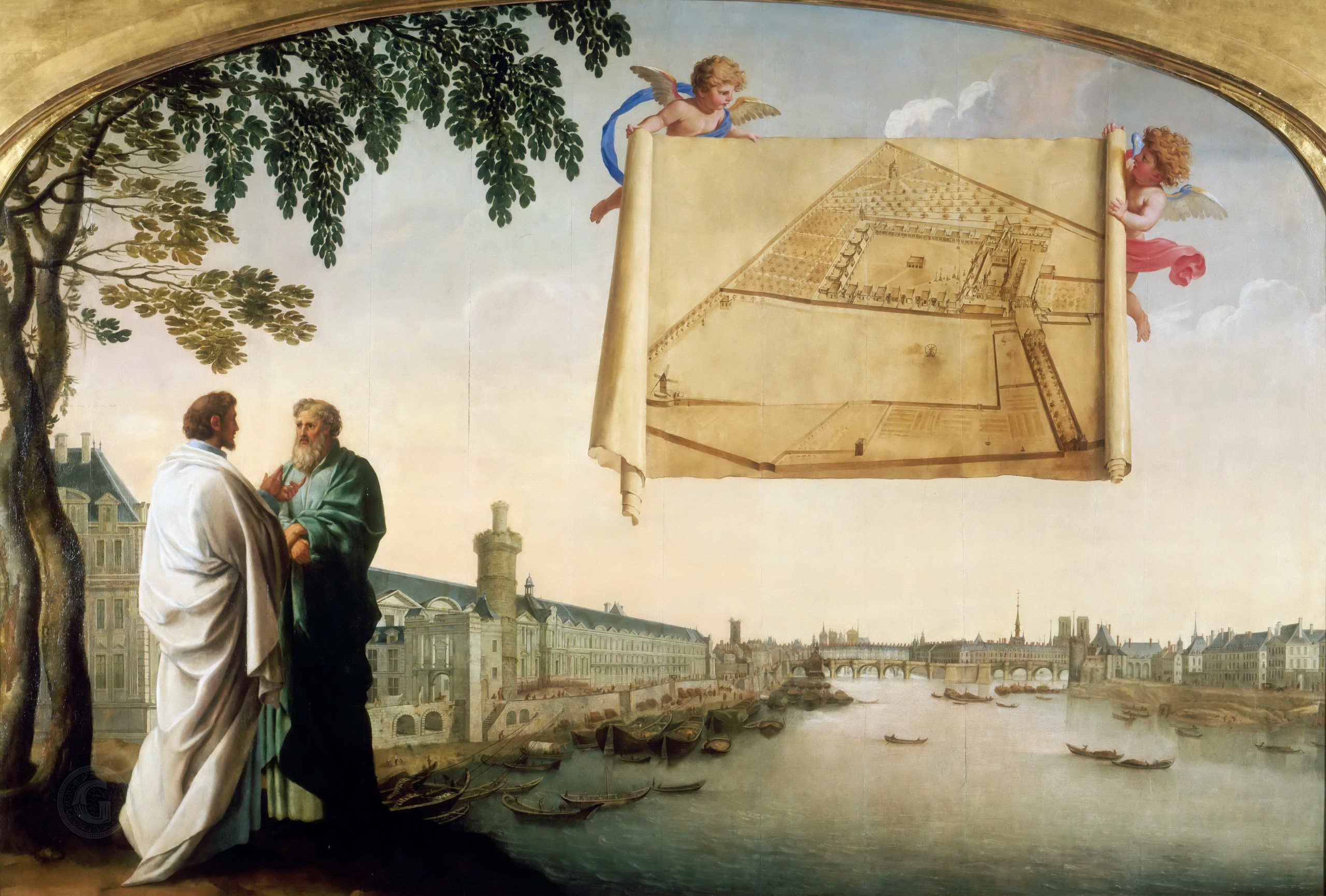

Eustache Le Sueur – Map of the Charterhouse of Paris

Eustache Le Sueur – Map of the Charterhouse of Rome

École de Sebron – Interior view of Milan Cathedral – 1841

Hubert Robert – Ruins with an obelisk in the distance – 1775

Giovanni Paolo Panini – Cardinal Melchior de Polignac visiting Saint Peter’s in Rome 1730

The beginnings of modern architectural representation

During the second half of the 18th century, a long debate occupied teachers and practitioners of the time concerning the place of the practice of drawing in the training of future architects.

Giovanni Bottari, a Florentine scientist, considered that to be good, an architect must above all be a good designer, but many detractors in Italy and in Spain contradict this thesis and are fundamentally wary of too much attention paid to this discipline. which in their eyes risks making students lose the technical and scientific qualities essential to a good architect.

Evolving between these two trends, architectural representation will gradually move closer to graphic arts.

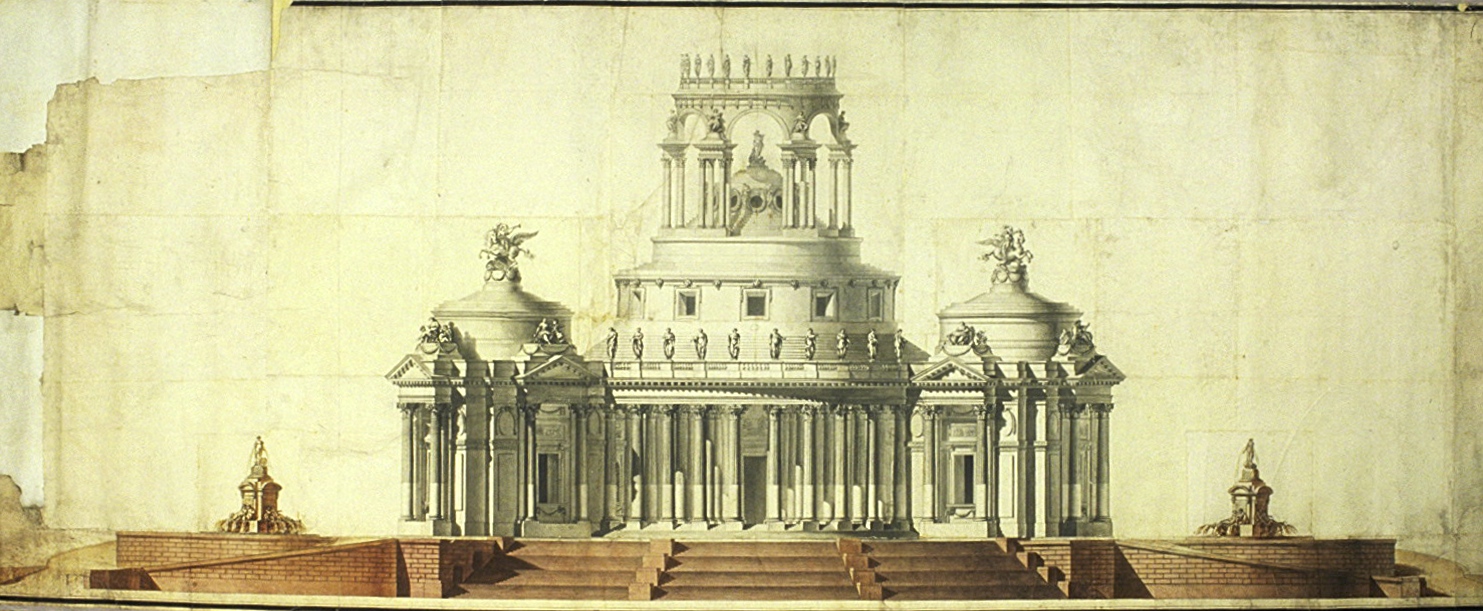

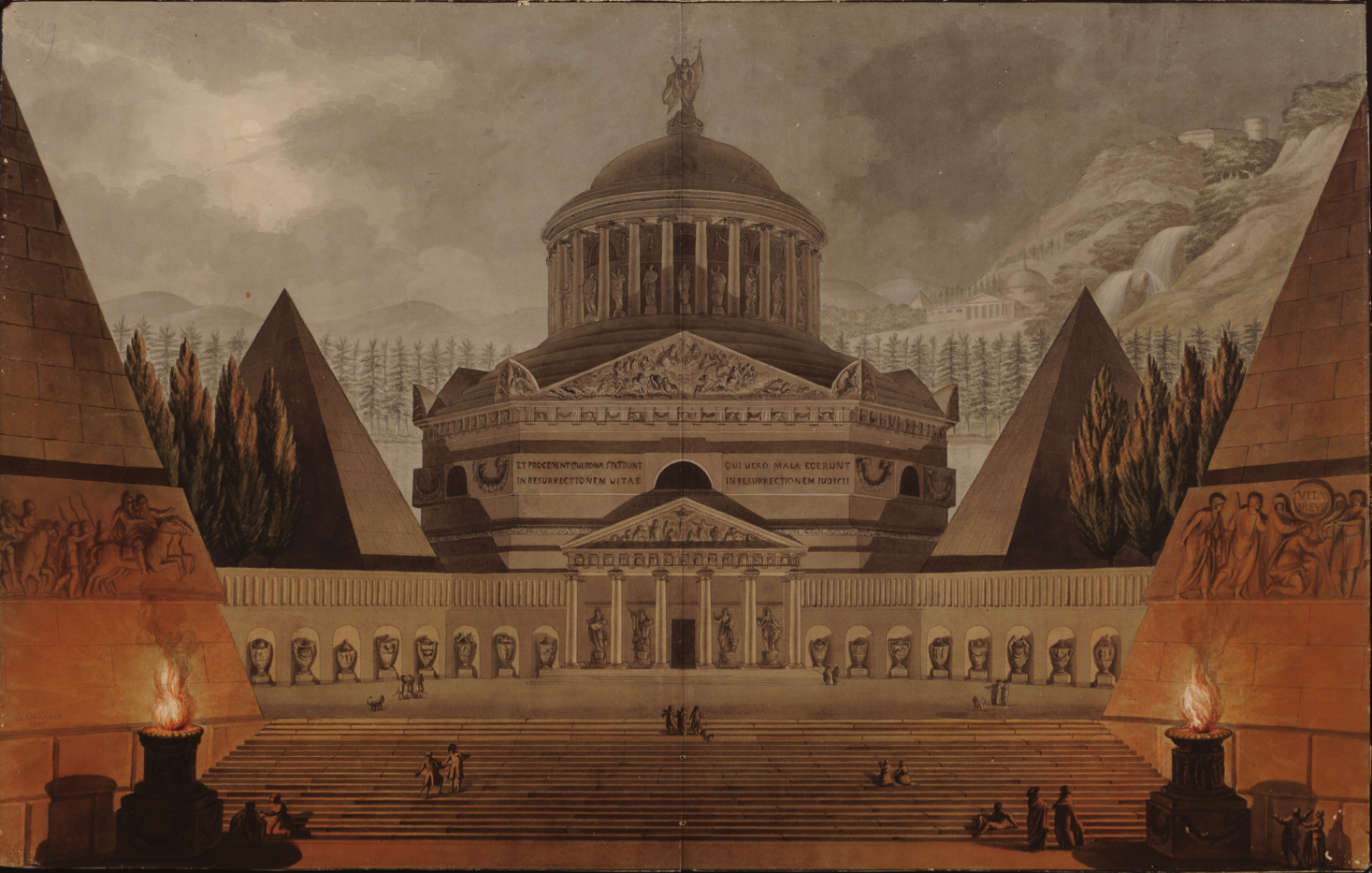

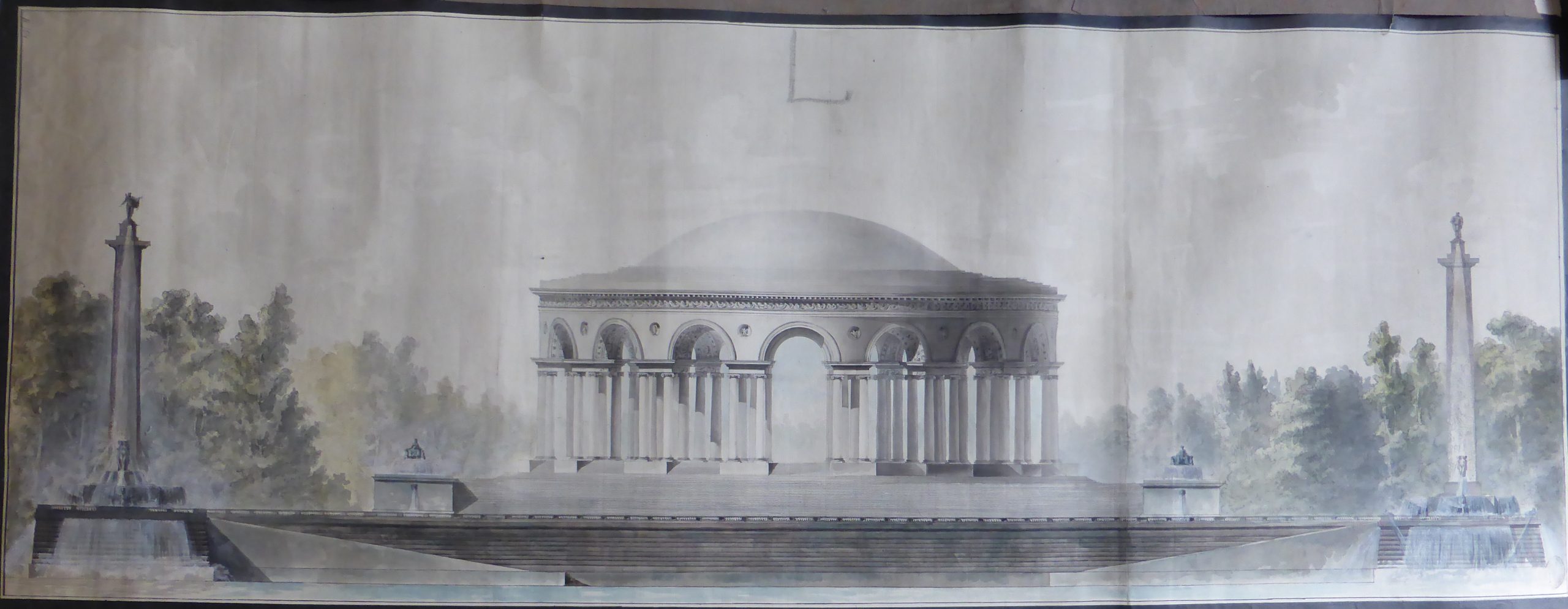

Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, A sepulchral monument for the use of the sovereigns of a great empire – 1785

And it is in France that this evolution was the most radical under the influence of the Royal Academy of Architecture which served above all to distinguish the best architects of the profession in view of working for royal projects. For this, the institution offered public lectures, architectural theory and mathematics in its premises at the Louvre and organized an annual drawing competition, the Grand Prix. Its evolution, compared to that of competitions in neighboring countries, makes it possible to understand the path taken by architectural representation in France.

Indeed it is very quickly unlisted images and clearly intended to seduce a possible client that will win the first places in these competitions. Then will come the increasingly frequent use of colors and landscape backgrounds.

Jean-René Billaudel, A living room for academies – 1754

Giovanni Campana, A sepulchral chapel – 1795

Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières wrote in The Genius of Architecture or the Analogy of This Art with Our Sensations in 1780:

“The most intelligent architect can only hope to succeed as long as he has made his drawing as a result of the exposure of the sun which illuminates the lateral parts of the building to be constructed. It is necessary that, like a skilful painter, he knows how to take advantage of the shadows, the lights, that he manages his tints, his degradations, his nuances, that he brings a true harmony to everything and that the general tone is clean and appropriate. ; he must have foreseen its effects and be as circumspect on all parts as if he had a picture to produce.”

Charles Percier, A menagerie – 1783

Architectural images as an art object

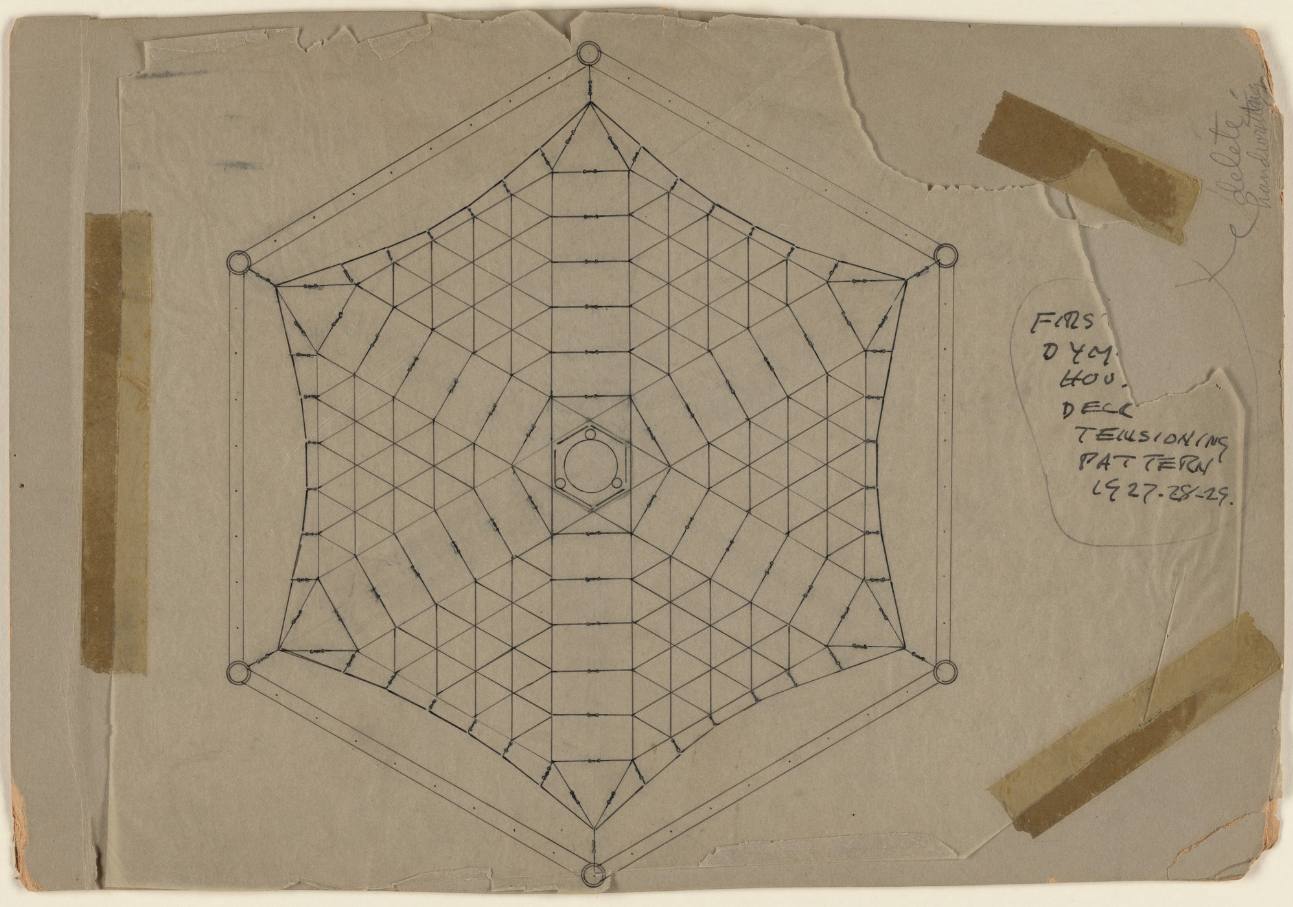

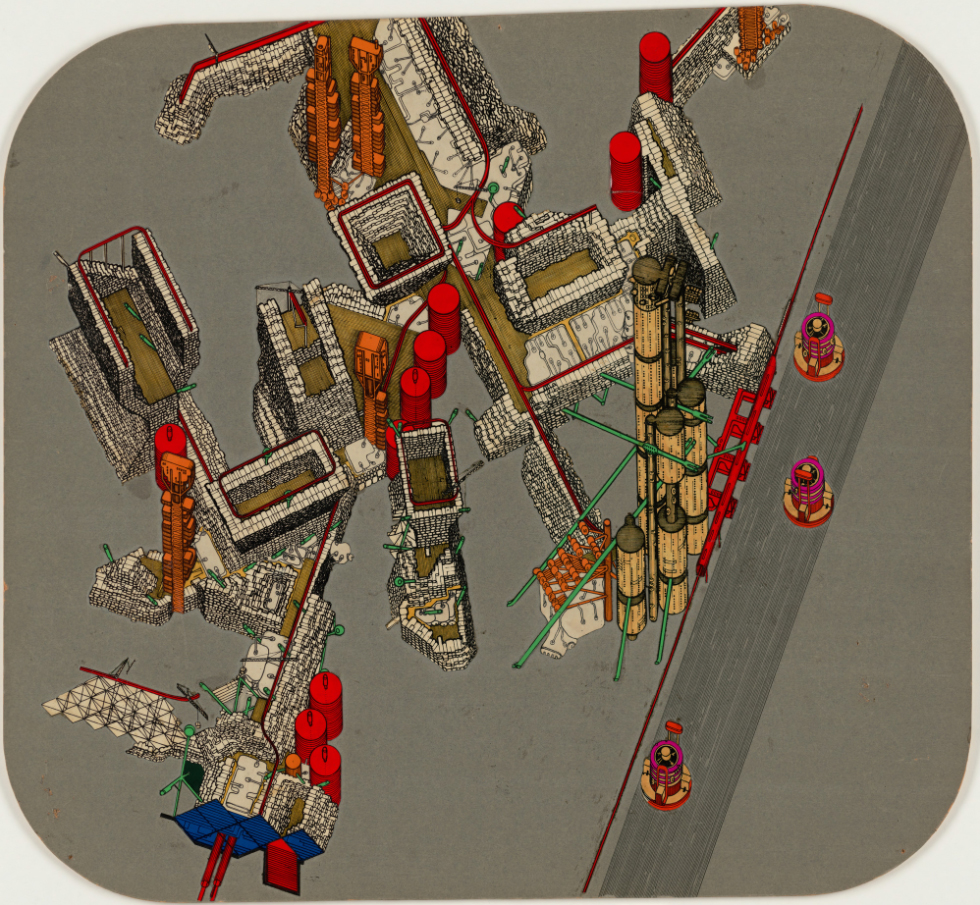

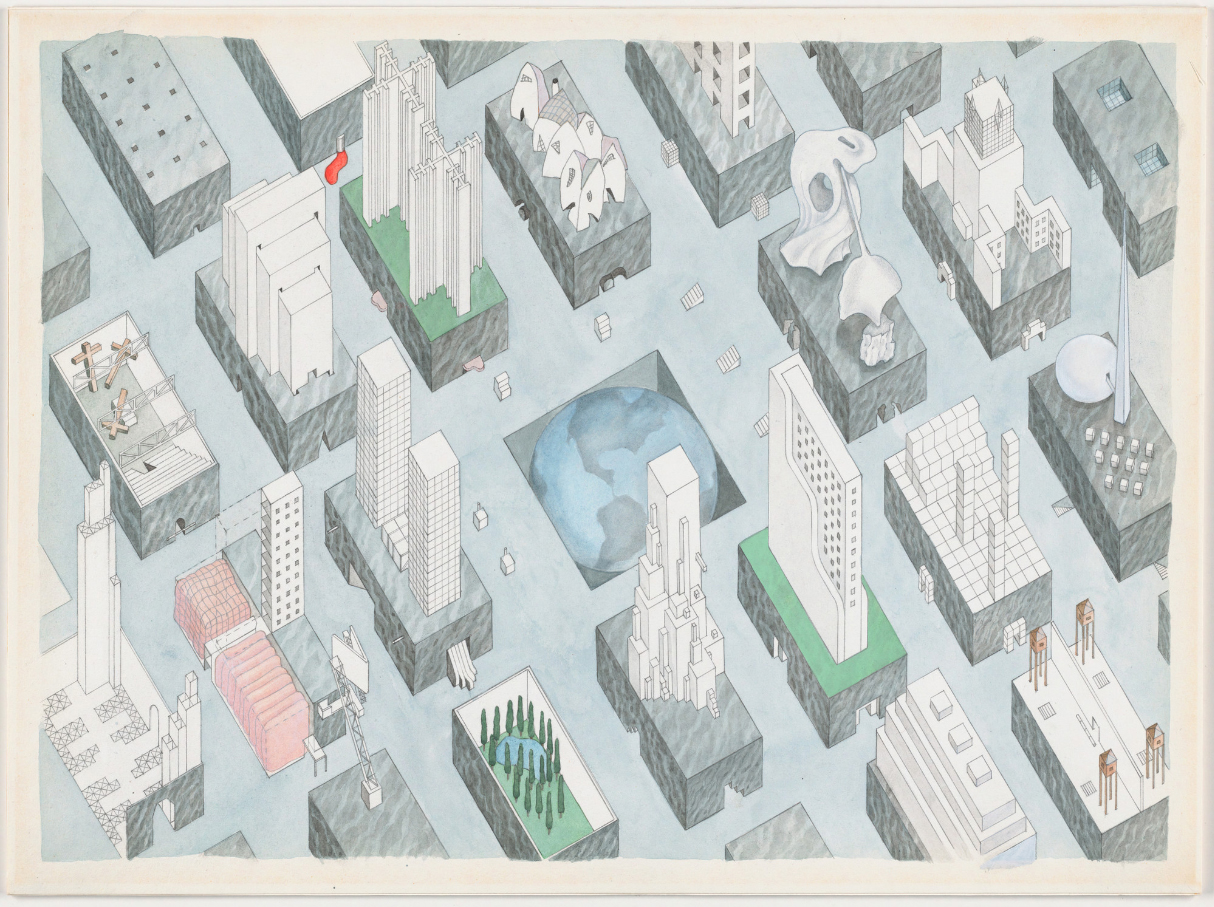

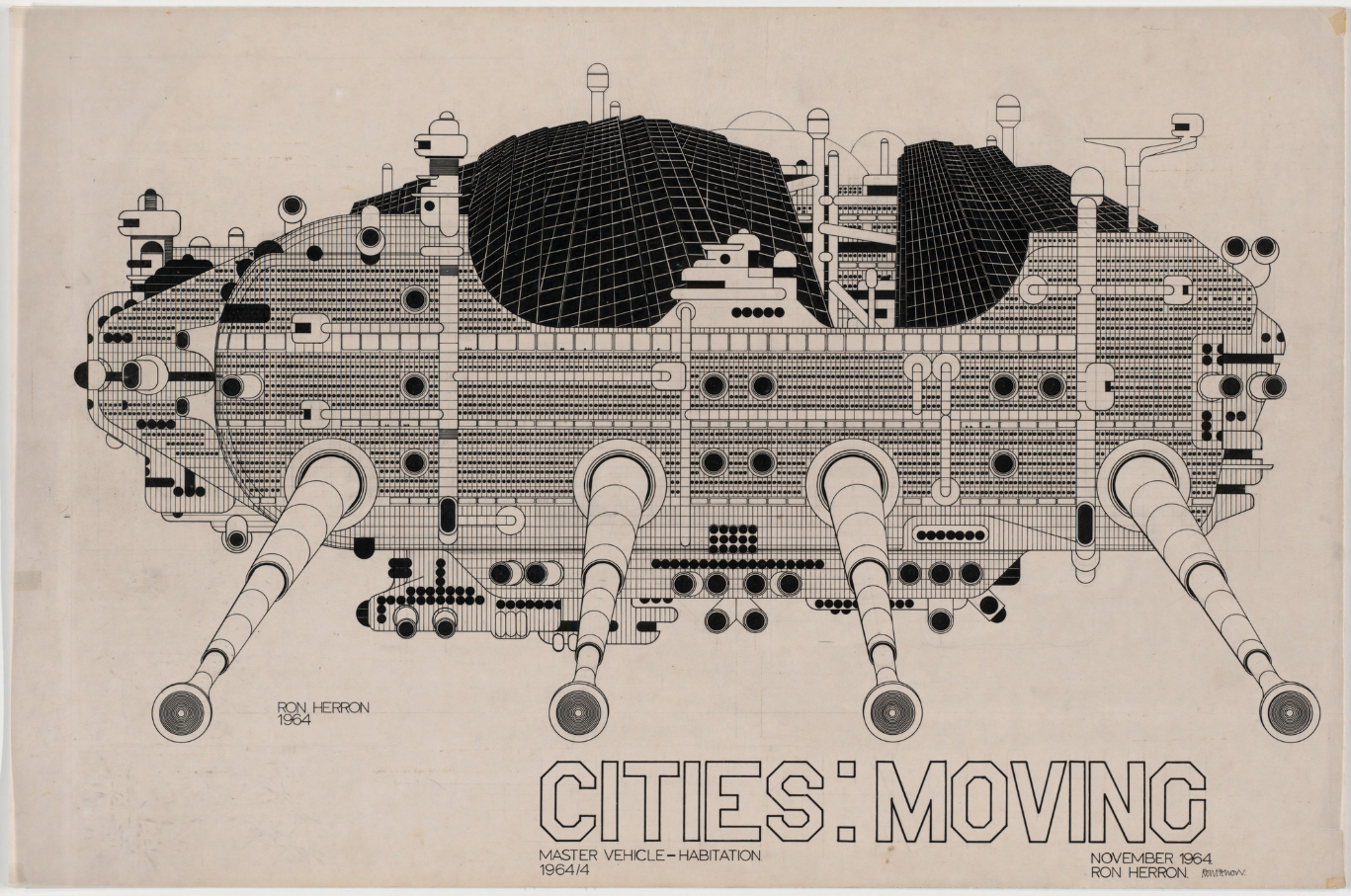

At the end of the 20th century a vast movement to rediscover the heritage of architectural representation emerged. Several institutions began to consider preparatory drawings as works in their own right and therefore sought to acquire more and more of them. In parallel with numerous private gallerist initiatives, we followed the same path by exhibiting and selling these drawings.

Furthermore, the debate on the place of drawing in architectural training ended up very clearly shifting to the advantage of the practice of drawing and the consideration of the latter as a subject of study in its own right. This evolution and the appearance of an ever-increasing number of architectural publications has therefore generated a notable increase in the practice and availability of these works.

But the truly notable phenomenon of the 70s and 80s is the accession and entry of these architectural drawings into the public and private collections of amateurs considering them at the same level as classic works of fine arts.

One of these early collectors is Barbara Pine who began to bring together the works of different contemporary architects in the early 1970s and, being on the board of MoMA, took an important part in the acquisition of architectural drawings for the museum.

Judith York Newman’s SPACED gallery in New York was founded a few years later, exhibiting drawings and models. His exhibitions brought these drawings into the sphere of works of art in the eyes of the public and critics more accustomed to the different trends of contemporary art.

The first MoMA sales of architectural drawings also date from this period (1975).

The following year, drawings from the École des Beaux Arts in Paris were presented at MoMA. Two hundred drawings are then exhibited, some dating from the Royal Academy. The effect was enormous and the museum’s bias usually anchored in the defense of a modern approach to art in opposition to the classicism and tradition which are the very definition of the Academy and subsequently of the École des Beaux Arts has propelled the discipline into the world of artistic controversies. But it is also on this occasion that the drawings are freed from their utilitarian aspect, from their purpose constructed to be considered, judged and appreciated only for themselves.

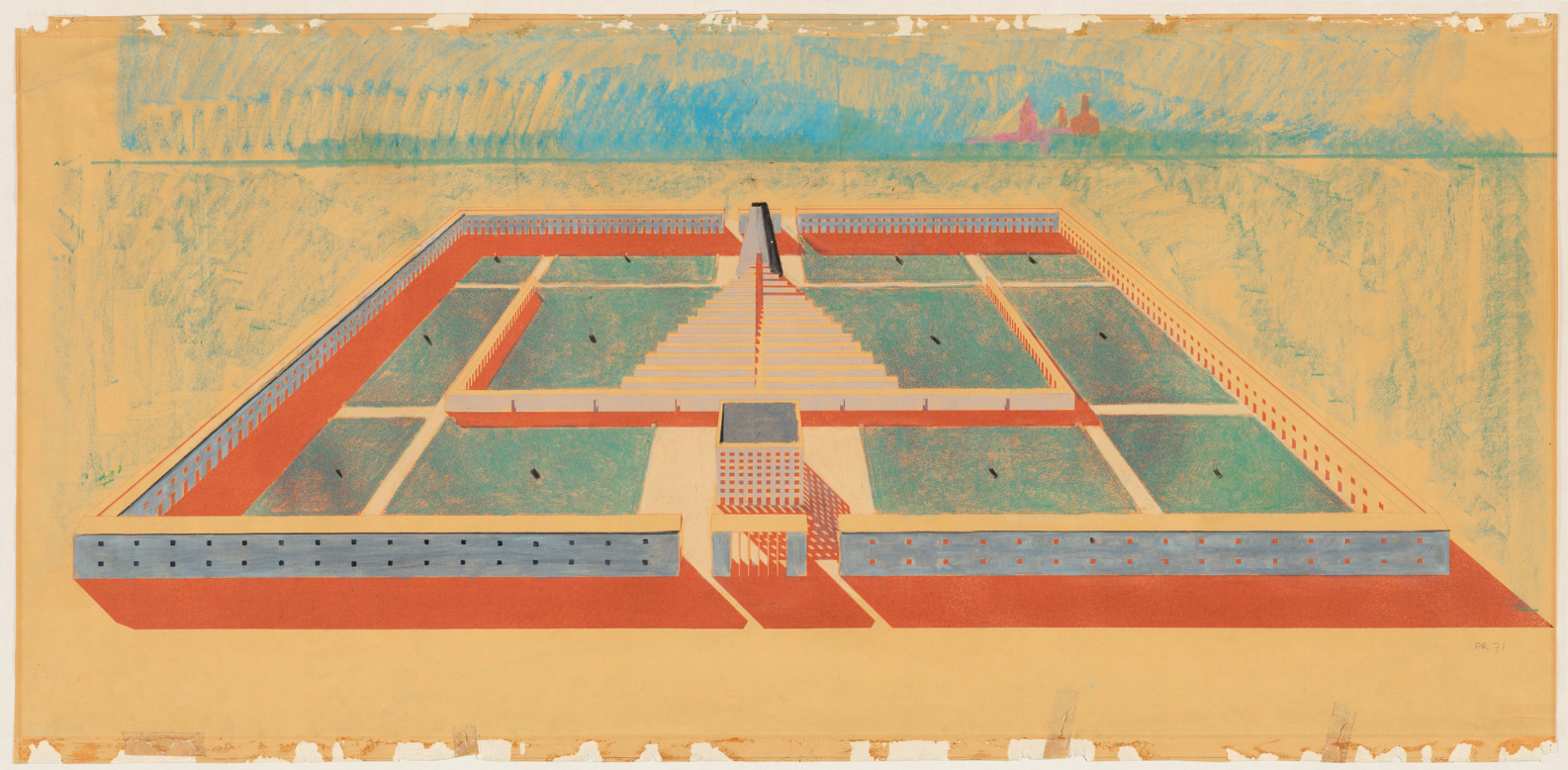

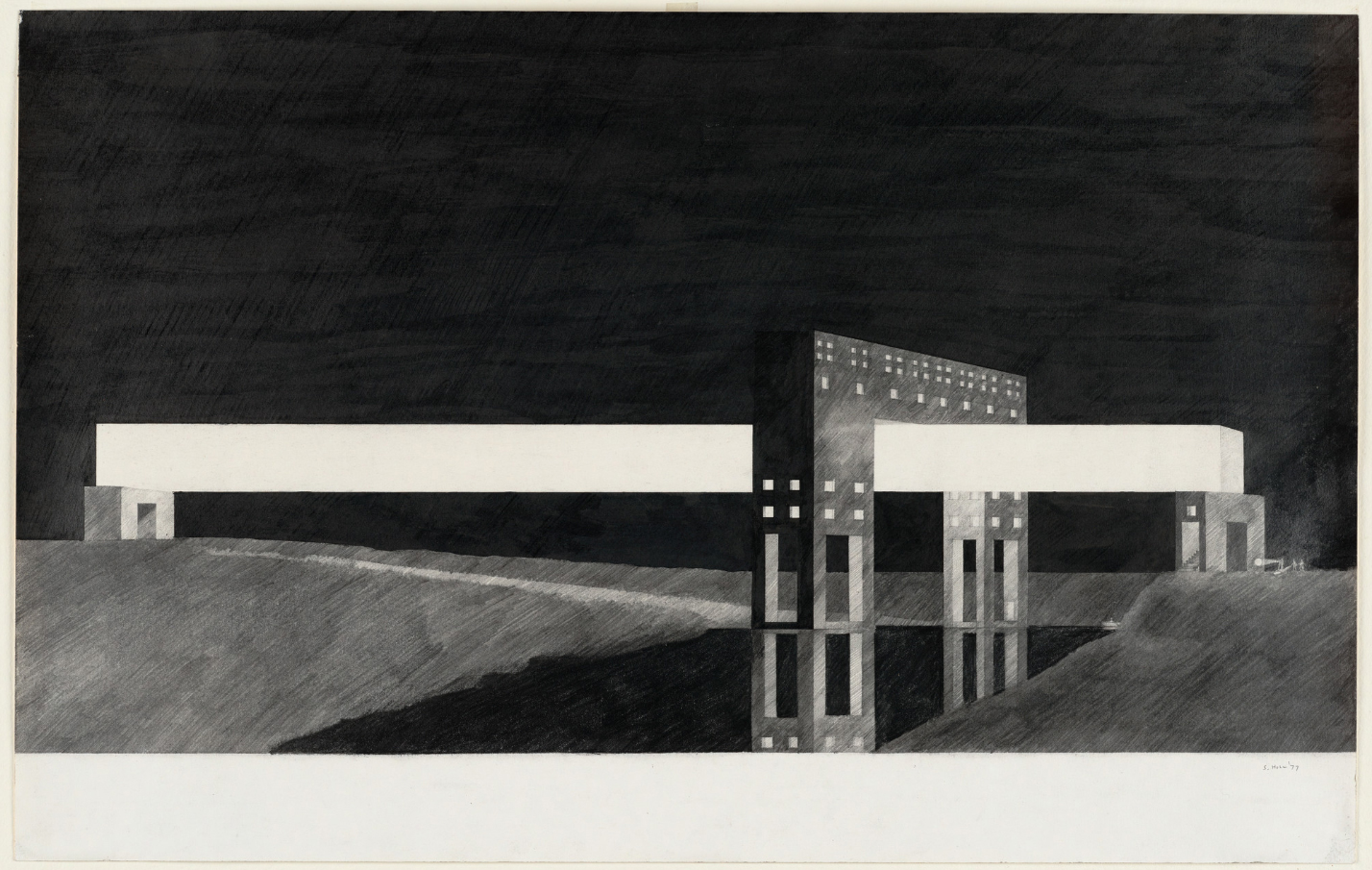

Aldo Rossi, Gianni Braghieri. Cemetery of San Cataldo, Modena, Italy, Aerial perspective. 1971

Sources :

L’image en architecture : De la représentation et de son empreinte utopique – J.- P. Jungmann

Basile Baudez, « L’Europe architecturale du second XVIIIe siècle : analyse des dessins »,

https://journals.openedition.org/lha/543

A Global History of Architectural Representations – Jordan Kauffman

https://gahtc.org/modules/preview/74